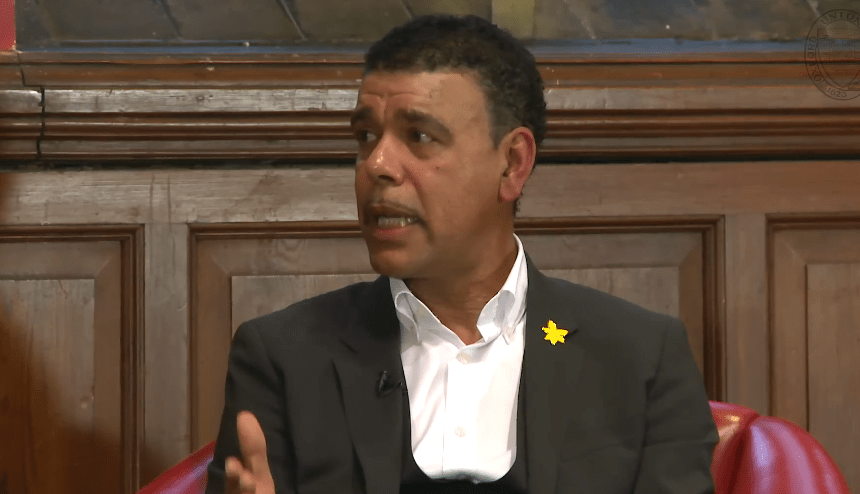

Credit: oxfordUnion

Chris Kamara’s illness began to appear not as a single dramatic event but as a string of small dislocations: a slurred phrase here, a pause there, the kind of subtle cadence change that, for a man whose profession was rapid-fire observation, is immediately conspicuous and deeply disorienting.

That gradual unpicking of fluency eventually produced a diagnosis: speech apraxia, a neurological disorder that disrupts the brain’s ability to programme and sequence the complex muscle movements required for speech.

| Label | Information |

|---|---|

| Name | Christopher Desmond “Chris” Kamara MBE |

| Born | 25 December 1957 — Middlesbrough, England |

| Occupation | Former professional footballer; Manager; Broadcaster; Pundit |

| Notable Work | Soccer Saturday (Sky Sports, 1999–2022); Goals on Sunday; Amazon Prime Boxing Day reporting (2024) |

| Reported Medical Issues | Underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) — April 2021; Speech apraxia diagnosed 2022; Dyspraxia affecting balance |

| Treatments & Routes | Speech and neurological therapy; specialist trips to Mexico for radio-frequency/magnetic-field treatment; rehabilitation and physiotherapy |

| Impact on Life/Work | Stepped back from regular presenting in 2022; selective return to broadcasting; altered mobility and selective work choices |

| Charitable Work | Patron of multiple charities; active fundraiser and community ambassador |

| Career Highlights | Over 600 league appearances; player, manager and long-time television favourite known as “Kammy” |

| Reference | Wikipedia — https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chris_Kamara |

The diagnosis arrived after an earlier finding — an underactive thyroid in 2021 — and the overlap of multiple conditions complicated both explanation and expectation, illustrating how medical narratives can unfold in stages and sometimes require prolonged, patient-centred detective work.

Kamara’s public account of that process has been candid and, at times, painfully honest: from the “brain fog” he described during interviews to the nights when intrusive thoughts led him to fear dementia or the idea that he had become a burden. Those admissions, shared with a typically self-deprecating warmth, revealed an emotional truth beneath the medical facts — namely, how identity and vocation can be eroded by conditions that silence a professional instrument.

Speech apraxia is not merely a problem of pronunciation; it is a planning disorder, a misfire in the pipeline from intention to articulation, and for a former broadcaster whose quick lines and catchphrases became cultural shorthand, the effect was existential as well as physical. Alongside apraxia, dyspraxia contributed balance and coordination issues, rendering stairs and tight spaces unpredictably hazardous and transforming ordinary tasks into exercises in concentration and caution.

Faced with that double burden, Kamara pursued a mix of conventional care and specialist interventions, including repeated trips to Mexico where targeted radio-frequency and magnetic-field therapies were reported to have helped restore fluency and pacing in his speech. Those journeys underline a contemporary reality: when faced with rare or stubborn neurological disorders, patients — even high-profile ones — often explore treatments beyond local provision, balancing evidence, hope and the pressure to act.

Progress has been real, if incremental. Kamara has described being up to “80 per cent better” in measures of speech after his Mexican treatments, and his return to broadcasting on Boxing Day 2024 was a deliberately staged step: a cautious, emotionally charged re-entry that signalled improvement without promising full restoration. He remains selective about work, choosing engagements that fit practical limits and preserve dignity, a decision that reframes ambition through the lens of sustainability rather than resignation.

There is a social lesson embedded in this personal arc. Kamara’s openness about his mental health struggles — the shame, the intrusive thoughts, the eventual acceptance that help was needed — normalises vulnerability in professions often conditioned to ignore it. His reflections about once being harsh on others who “didn’t want to train” show how lived experience can flip perspective; having suffered, he now speaks with a more empathetic cast, urging people to talk, to accept care, and to reject the stigma that makes asking for help feel like failure.

Professional solidarity has been decisive. Colleagues such as Jeff Stelling and Ben Shephard publicly and privately supported Kamara, offering practical aid and a compassion that blurred the line between workplace and community. That network of support — friends, family, clubmates, broadcasters — functioned as a non-clinical safety net and, Kamara has said, conferred the rare experience of receiving accolades while still alive, a small but resonant reversal of the usual posthumous praise.

Kamara’s narrative also raises questions for employers and broadcasters: how should media organisations detect early signs, make reasonable adjustments, and craft phased returns without trivialising expertise or penalising talent for illness? Contracts, insurance and occupational-health pathways must adapt so that people whose tools are speech or movement can be accommodated with dignity, supported by rehabilitation and given options for reduced or modified duties. Concrete structural changes here would be particularly beneficial for mid-career professionals whose livelihoods depend on visibility and performance.

Another strand of reflection concerns diagnostic humility. Kamara’s pathway from thyroid treatment to apraxia diagnosis highlights how overlapping conditions can obscure causation, and how timely referral to neurological specialists can prevent years of ineffective treatments and the attendant deterioration in wellbeing. For clinicians and patients alike, his case argues for careful listening, iterative testing and a readiness to revise hypotheses when symptoms evolve.

Finally, the philanthropic turn in Kamara’s response is strikingly forward-looking: instead of withdrawing after illness, he has channelled experience into advocacy and charity, continuing to support causes close to his heart and using his platform to normalise help-seeking. In doing so he reframes illness not as an endpoint but as a catalyst for new purpose, reshaping a public persona into a vehicle for empathy and practical aid for others facing invisible and destabilising conditions.

Chris Kamara’s illness therefore reads as a series of interconnected lessons — medical, professional and social — about how societies respond to neurological impairment, how workplaces can better protect those whose livelihoods depend on speech and movement, and how personal crisis, when publicly navigated with candour and support, can produce a broader, more humane conversation about care, dignity and second chances.