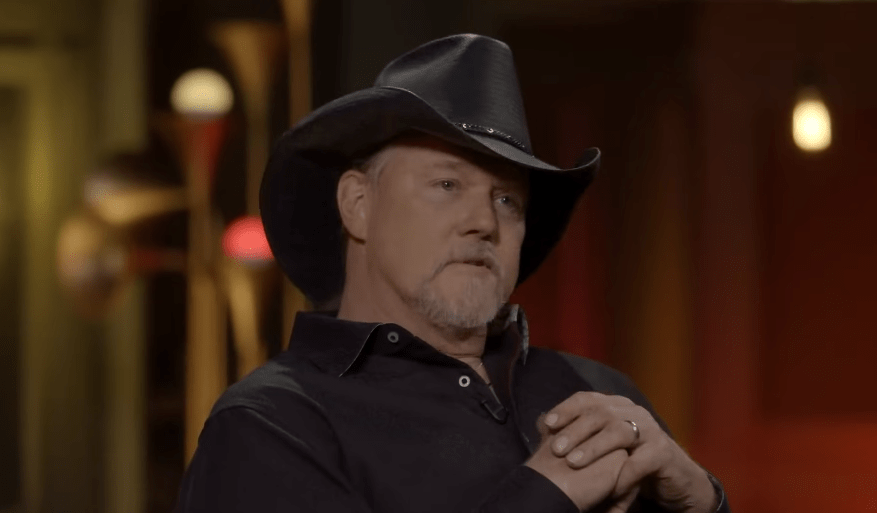

Credit: Circle Country

Every few years, questions about Trace Adkins’ illness seem to arise at remarkably similar times, usually after he changes in appearance, his tour becomes quieter, or there is a lull that allows rumors to spread like a bee colony sensing an open area.

Adkins’ story is notably fragmented, shaped by accidents, recovery, addiction, and discipline rather than a single clearly labeled condition, in contrast to performers whose health narratives revolve around a single diagnosis.

| Item | Details |

|---|---|

| Bio | Trace Adkins, born January 13, 1962, American country singer and actor |

| Background | Raised in Sarepta, Louisiana; former oil rig worker before music career |

| Career highlights | Multiple No. 1 country hits; Grand Ole Opry member; film and television roles including Monarch |

| Reference | Poeple.com |

His body was already enduring punishment long before he was recognized, working on oil rigs where danger was commonplace and injuries were viewed as inconvenient delays rather than warnings.

A bulldozer accident in the early 1980s almost cost him both legs, and shortly after, an oil tank explosion crushed his left leg. These incidents would have changed most people’s lives forever.

Instead of backing down, he continued forward with the assurance of someone who had great faith in his own fortitude, despite evidence to the contrary.

His pinky finger was severed in another incident while he was using a knife to open a bucket. It was surgically reattached at an angle to allow him to continue playing the guitar, which was a particularly creative and useful decision.

By the time he arrived in Nashville in the early 1990s, his body was marred by dents like old ones on a truck, but it was still very sturdy and functional, albeit subtly changed in ways that only the driver really knew.

When talking about his health, the most frequently mentioned incident occurred in 1994 after an alcohol-fueled argument resulted in him being shot in the chest, with the bullet going through his heart and lungs.

Although his recovery was remarkably successful, the emergency open-heart surgery that saved his life left him with long-lasting effects, such as constant cardiac monitoring and an unavoidable awareness of how narrow survival can be.

Although that shooting is frequently dismissed as an incident, its consequences were long-lasting, changing his perspective on risk, pain, and the appearance of control.

Long a part of his life, alcohol grew stronger with success, eventually turning into its own disease that subtly undermined everything else.

He entered rehab in 2001 as a result of a family intervention; this decision was motivated by necessity rather than image management, and the results were significantly better.

After a public altercation on a cruise ship in 2014, a second rehab stay felt different, indicating acceptance that sobriety was a continuous maintenance process rather than a short-term solution.

I recall thinking about how composedly he discussed physical pain that would have chilled most people when he later stated that broken hearts hurt more than broken bones.

Instead of striving for perfection, Adkins has since compared maintaining health to maintaining heavy machinery, simplifying routines, and releasing energy.

Healthy routines and daily structure have proven to be very effective in stabilizing both body and mind, and his marriage to actress Victoria Pratt has been a part of that reorientation.

Rumors of illness have been raised by his weight fluctuations in recent years, but people close to him have presented the change as deliberate, the outcome of lifestyle changes that were surprisingly inexpensive in effort but had a big impact.

Adkins’ problems are cumulative, a ledger of past harm that calls for awareness, pacing, and respect rather than treatment, in contrast to artists dealing with progressive illness.

He still performs and tours, but the rhythm has been significantly improved for sustainability, with recuperation incorporated into previously excessive schedules.

Age and experience have deepened his gravelly voice, which is sometimes misinterpreted as a sign of decline when, in fact, it is a reflection of endurance layered over scar tissue.

There is no longer any claim to invincibility, and that absence feels especially helpful, substituting steadiness for bravado without devolving into fragility.

Adkins’ admission that he is lucky to still be alive comes across as an accounting statement rather than a poetic statement, acknowledging that the odds could have gone against him.

For him, being healthy is about being functional, showing up for work, family, and responsibilities while being honest about one’s limitations.

His support of food allergies, motivated by his daughter’s illness, reveals a markedly enhanced awareness of vulnerability that previously might have been at odds with his persona.

Questions about his illness continue to be raised, which is indicative of a larger unease with narratives that defy extremes and provide steady progression rather than tragedy or miracle.

That middle ground is occupied by Adkins, who was molded by survival, which required adaptation rather than praise.

What’s still remarkable is how little he dramatizes any of it, preferring to continue working, adapting, and honoring a body that retains every blow.

Trace Adkins’ health story demonstrates that longevity can occasionally depend less on luck and more on knowing when to slow down. It is not about decline or redemption, but rather about moving forward with accumulated damage.